Terminology

On the Terms Costanoan, Ohlone, Ramaytush, and Yelamu

Some lack of clarity persists regarding the choice of terminology used to identify the Costanoan-speaking peoples of the San Francisco Bay Area and the original peoples of the San Francisco Peninsula. Inaccurate terminology, like the use of Muwekma Ohlone to identify the original peoples of the San Francisco Bay Area, still linger in various public venues and documents. The following provides basic information and guidelines regarding the language used to identify the Costanoan-speaking peoples of the San Francisco Bay Area in general and of the Ramaytush Ohlone in particular.

As far as we know, not all the original peoples of the San Francisco Bay Area had names for themselves as distinct groups of people, but our present need for collective identifiers has created a number of terms used to refer to historical and contemporary Bay Area Native peoples. Like most California Natives, contemporary Ohlone peoples use linguistic boundaries instead of local tribal boundaries to define their respective tribal territories. Because there are so few living descendants of the original peoples of California, surviving descendants from local tribes tend to represent the interests of their linguistic areas as territories.

For example, descendants of the village of Timigtac in Aramai territory tend to identify as Ramaytush in order to represent the ancestors of the local tribes along the San Francisco Peninsula, all of whom intermarried, shared a common culture, and spoke the same dialect of the Costanoan language. Since the lineage from Timigtac is the only known surviving lineage within Ramaytush territory, their descendants speak on behalf of all Ramaytush peoples. That practice is common across California and derives from an understanding of Indigenous identity based on substantial documented evidence of lineal descent from a California Native. As such, one’s ancestral homeland refers not only to the geographic boundaries of their ancestral tribe of origin but to the broader ethnic or linguistic territory within which their ancestral tribe of origin is located.

Since honoring one’s ancestor remains an important objective of all California Natives, respect for another’s ancestors and territories remains a critical component of Indigenous protocol and should be upheld by non-Native agencies and organizations as well. At minimum non-local Indigenous persons and groups should acknowledge one another’s territory when visiting and should ask permission to conduct ceremony or other Native activities. Additionally, Natives and non-Natives should acknowledge territory properly and should strive for historical accuracy so as to avoid the disharmony that often results from violations of protocol and to avoid misinforming the broader public.

As far as we know, not all the original peoples of the San Francisco Bay Area had names for themselves as distinct groups of people, but our present need for collective identifiers has created a number of terms used to refer to historical and contemporary Bay Area Native peoples. Like most California Natives, contemporary Ohlone peoples use linguistic boundaries instead of local tribal boundaries to define their respective tribal territories. Because there are so few living descendants of the original peoples of California, surviving descendants from local tribes tend to represent the interests of their linguistic areas as territories.

For example, descendants of the village of Timigtac in Aramai territory tend to identify as Ramaytush in order to represent the ancestors of the local tribes along the San Francisco Peninsula, all of whom intermarried, shared a common culture, and spoke the same dialect of the Costanoan language. Since the lineage from Timigtac is the only known surviving lineage within Ramaytush territory, their descendants speak on behalf of all Ramaytush peoples. That practice is common across California and derives from an understanding of Indigenous identity based on substantial documented evidence of lineal descent from a California Native. As such, one’s ancestral homeland refers not only to the geographic boundaries of their ancestral tribe of origin but to the broader ethnic or linguistic territory within which their ancestral tribe of origin is located.

Since honoring one’s ancestor remains an important objective of all California Natives, respect for another’s ancestors and territories remains a critical component of Indigenous protocol and should be upheld by non-Native agencies and organizations as well. At minimum non-local Indigenous persons and groups should acknowledge one another’s territory when visiting and should ask permission to conduct ceremony or other Native activities. Additionally, Natives and non-Natives should acknowledge territory properly and should strive for historical accuracy so as to avoid the disharmony that often results from violations of protocol and to avoid misinforming the broader public.

|

Costanoan

The term Costanoan derives from the Spanish costaños, which means “coastal people”; it is a linguistic term used to designate a particular “language family.”[i] The Costanoan language family consists of six distinct languages: Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, Chalon, and the San Francisco Bay language that contains three dialects spoken in the San Francisco Bay Area: Chochenyo in the east, Tamien in the southeast, and Ramaytush along the San Francisco Peninsula.[ii] According to Levy, “the Costanoan-speaking people lived in approximately 50 separate and politically autonomous nations or tribes” at the time of contact, although that total depends upon how a tribe is defined and measured.[iii] |

|

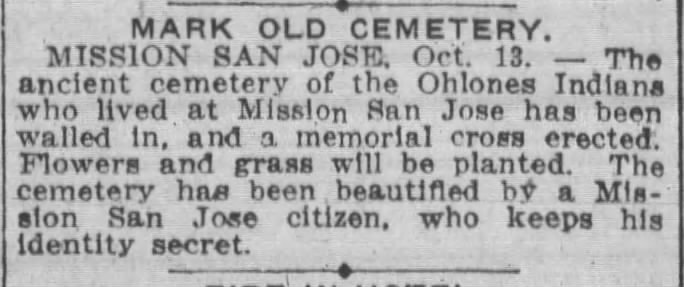

"Mark Old Cemetery," Oakland Tribune, October 13, 1915. Although not the first misspelling of the word, Oljon, this misspelling (Ohlone) came into common usage in the early 1900s.

|

Ohlone

The term Ohlone resulted from a misspelling of Oljon, a tribe within Ramyatush territory along the Pacific Coast. The switch from “Oljon” to “Ohlone” first occurred in the mid-1800s and was repeated thereafter in other publications.[iv] It rose to prominence as substitute an identifier especially among East Bay Chochenyo descendants in the early 1900s. Today it is broadly accepted as an identifier for all Costanoan-speaking peoples from the San Francisco Bay Area to Big Sur, although some persons and groups, like the Amah Mutsun and Tamien Nation, prefer not to use Ohlone as an identifier. |

|

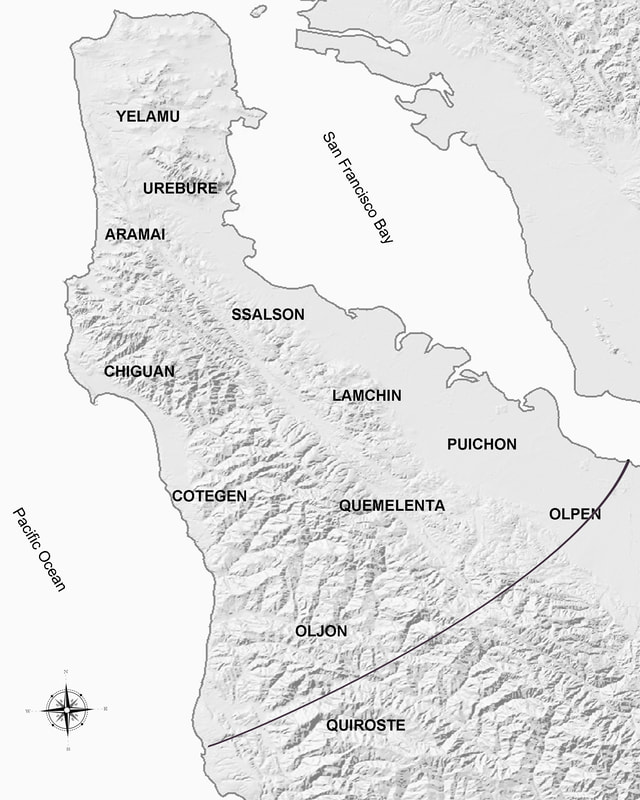

Ramaytush

The term Ramaytush (pronounced “rah-my-toosh”) is commonly used as a designation for a dialect of the Costanoan language that was spoken by the original peoples of the San Francisco Peninsula (Figure 1). Richard Levy first used the term in 1978, but his usage derives J.P. Harrington’s interviews with Chochenyo speakers Angela Colos and Jose Guzman. Harrington’s notes that rámai refers to the San Francisco side of the San Francisco Bay and –tush is the Chochenyo suffix for people. Thus, rámáitush referred to the people of the San Francisco Peninsula.[v] Most descendants of the Costanoan-speaking groups of the San Francisco Bay Area, however, refer to themselves as Ohlone, hence the phrase, Ramaytush Ohlone. The entire San Francisco Peninsula is Ramaytush Ohlone territory. All persons Indigenous to the San Francisco Peninsula should be identified either as Ramaytush or by their local tribal name. The local tribes whose members spoke the Ramaytush dialect include the Aramai, Chiguan, Cotegen, Lamchin, Olpen, Puichon, Ssalson, Olpen, Urebure, and Yelamu. |

|

Updated Map Coming Soon

|

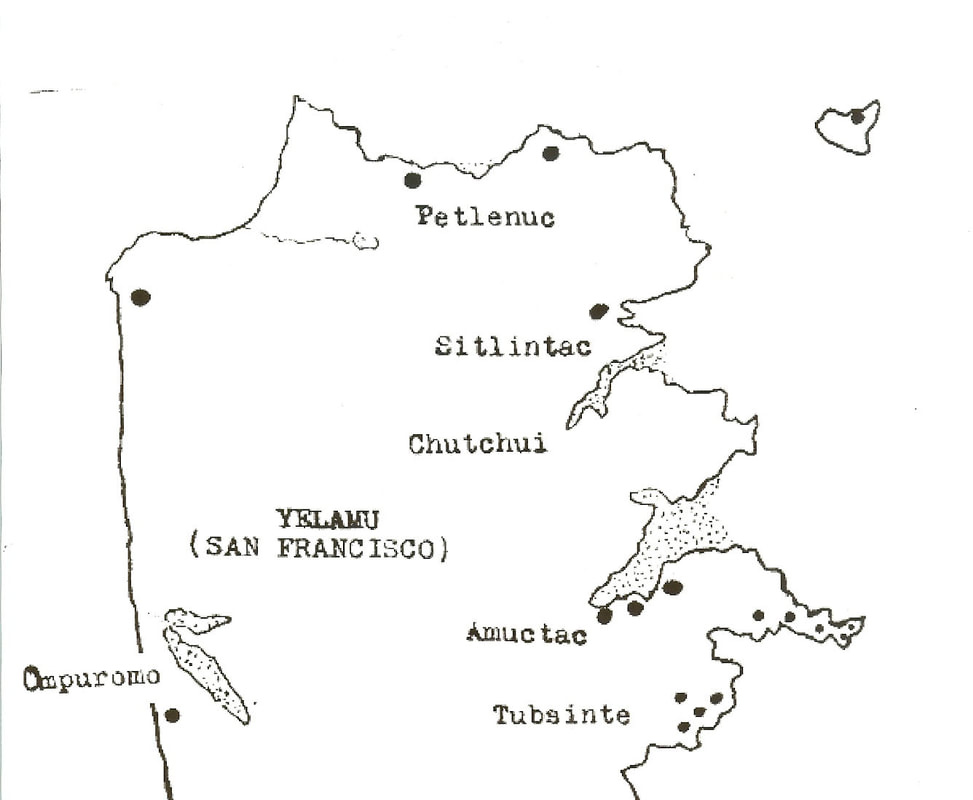

YelamuIn contemporary usage, Yelamu refers to a people and to a territory. Yelamu refers to the original peoples of the territory within the boundaries of what is now the County of San Francisco. The Yelamu are considered to be an independent tribe of the Ramaytush Ohlone peoples because they spoke the Ramaytush dialect of the San Francisco Bay Costanoan language.

When reconstructing the independent tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula, anthropologist and ethnohistorian Randall Milliken used the word Yelamu to refer to the original peoples of what is now San Francisco County. According to Milliken, “Yelamu is a cover term for the tribe that held the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula” (1995:260). The southern boundary of Yelamu drawn by Milliken conforms to southern edge of San Francisco County. The word Yelamu was extracted from the mission registers of Mission Dolores and refers to a place, and likely a village, whose location is unknown. Since the independent tribes of the Ramaytush Ohlone typically did not have a name for themselves as a tribal community, Milliken and other researchers assigned them a name and a territorial boundary based on physio-graphic features. In making that assignment, the researchers assumed that particular groupings of individual villages formed a tribal community. There is, however, no proof that the original peoples of San Francisco County were in fact a group of villages united in some way as a tribal community. We do know that some villages had their own independent leaders. For example, the villages of Petlenuc and Chutchui had their own tribal leaders, but shared the seasonal village of Sitlintac. Does that make them a tribe or tribal community? Other villages to the south within Yelamu territory may have been united as a distinct tribal community as well, but we cannot know for certain. As stated above, we use the term Yelamu to refer to the original peoples who once lived within the present boundaries of San Francisco County. They are considered to be an independent tribe of the Ramaytush Ohlone peoples of the San Francisco Peninsula. Also, Yelamu refers to the territory within the current boundaries of the County of San Francisco. Yelamu is used as the native name for the City and County of San Francisco. |

References

[i] Levy, Richard. “Costanoans,” in Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1978, 485.

[ii] Milliken, Randall. A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1769-1810. Ballena Press Anthropological Papers, No. 43. Menlo Park, CA: Malki Museum, 2009, 5.

[iii] Levy, Handbook, 485.

[iv] Johnston, Adam. “Costanos” [San Francisco Costanoan vocabulary] by Pedro Alcantara, in Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, ed. Henry R. Schoolcraft. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippencott, 504.

[v] Milliken, Randall, Laurence H. Shoup, and Beverly R. Ortiz. Ohlone/Costanoan Indians of the San Francisco Peninsula and Their Neighbors, Yesterday, and Today. Archaeological and Historical Consultants. Oakland, CA, 2009, 289.

[ii] Milliken, Randall. A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1769-1810. Ballena Press Anthropological Papers, No. 43. Menlo Park, CA: Malki Museum, 2009, 5.

[iii] Levy, Handbook, 485.

[iv] Johnston, Adam. “Costanos” [San Francisco Costanoan vocabulary] by Pedro Alcantara, in Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, ed. Henry R. Schoolcraft. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippencott, 504.

[v] Milliken, Randall, Laurence H. Shoup, and Beverly R. Ortiz. Ohlone/Costanoan Indians of the San Francisco Peninsula and Their Neighbors, Yesterday, and Today. Archaeological and Historical Consultants. Oakland, CA, 2009, 289.